Modern analytics is becoming increasingly powerful. High-resolution LC/MS systems, complex software, automated methods—technologically speaking, many laboratories today are at an impressive level. And yet one central problem remains unsolved: knowledge management in the laboratory.

A device alone does not guarantee quality. Without structured laboratory management and active quality management, even the best system becomes a risk.

When technology grows faster than knowledge

The purchase of a state-of-the-art LC/MS system is a strategic decision. It expands the analytical spectrum, enables new method developments, and strengthens competitiveness. However, as the complexity of the devices increases, the demands on operation, methodology, and troubleshooting also rise exponentially.

In this context, small gaps in knowledge suddenly have a big impact:

- Incorrectly selected parameters lead to failed runs

- Repeat analyses cause loss of time and material

- Unnecessary service calls generate high costs

- Uncertainty within the team leads to declining efficiency

- Documentation gaps create compliance risks

This is not a hardware problem. It is a knowledge and organization problem. The technological capabilities of a system can only be accessed if the necessary knowledge is systematically built up, documented, and made available.

Around 80% of laboratory users report critical knowledge dependencies on individual persons. Systematically managing and making knowledge available in the laboratory reduces these dependencies—and at the same time lowers the rate of unnecessary service calls.

Why technology alone does not produce quality

In regulated environments—whether under GMP, ISO 17025, or ISO 15189—the reproducibility of results is not only a scientific requirement but also a regulatory one. However, even a state-of-the-art analyzer will only deliver reliable results if it is operated, maintained, and used methodically.

The quality of analytical work depends on several factors:

Understanding of methods: Knowledge of separation mechanisms, ionization processes, and matrix effects is crucial for method development and validation.

Device competence: The practical ability to operate the system, adjust parameters, and recognize deviations must be present.

Troubleshooting ability: In the event of unexpected results or system errors, the team must be able to systematically identify causes and implement solutions.

Documentation discipline: All interventions, adjustments, and observations must be documented in a comprehensible manner.

If even one of these components is missing, a precision instrument becomes a black box whose results may be technically correct, but whose reliability cannot be guaranteed.

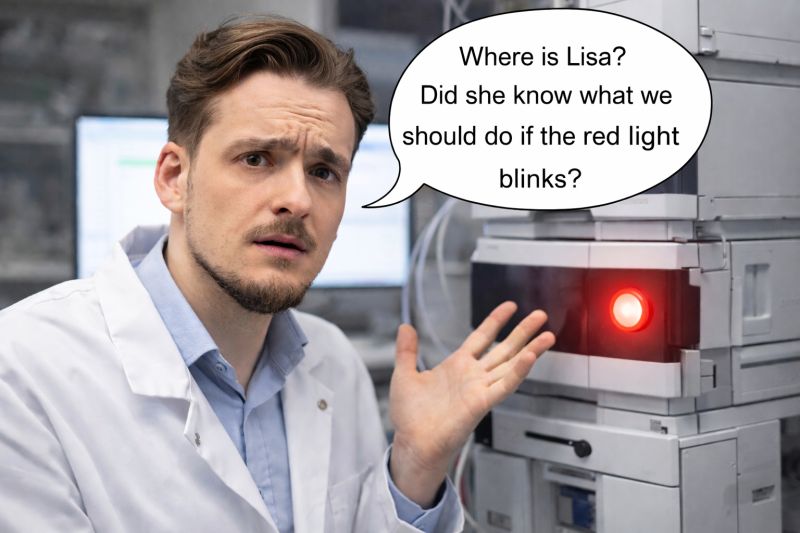

The "key user risk" in laboratories

In many laboratories, operational knowledge is concentrated in the hands of a few individuals. The experienced employee who has been maintaining the LC/MS for years becomes an indispensable resource. She knows the idiosyncrasies of the system, knows which parameters work with which matrix, and can often solve problems intuitively.

This model works—as long as that person is available. If they are absent due to illness, change employers, or retire, a vacuum is created. The knowledge does not exist in documented form, but only in the mind of a single person.

The consequences are significant:

Business interruptions: Critical analyses cannot be performed because no one has the necessary knowledge.

Quality issues: Less experienced employees make decisions based on incomplete information.

Inefficient training: New team members need months to acquire the necessary knowledge—through trial and error rather than structured knowledge transfer.

Compliance risks: Without documented procedures and knowledge bases, decisions cannot be justified to auditors in a comprehensible manner.

This key person risk is neither scalable nor compatible with the requirements of modern quality management laboratory systems. In regulated environments where test equipment monitoring, documentation, and traceability are crucial, it becomes a compliance issue.

How knowledge gaps affect quality, costs, and compliance

The effects of inadequate knowledge management can be described in three dimensions:

quality dimension

Insufficient knowledge leads to errors in method execution. Incorrectly selected columns, unsuitable solvent gradients, or incorrect mass spectrometer settings produce inaccurate or invalid results. This results in failed validations, out-of-specification results, or, in the worst case, incorrect analytical statements that are propagated through subsequent processes.

cost dimension

Repeat analyses due to avoidable errors cause direct costs: reagents, consumables, working time. Added to this are indirect costs due to delayed project completions, unplanned service calls, and inefficient use of resources. A system that is not used optimally due to knowledge deficits pays for itself much more slowly than planned.

Compliance dimension

Regulatory requirements demand traceable, documented processes. If knowledge only exists implicitly, there is no basis for consistent SOPs, traceable method development, and justifiable deviations. Audits reveal these gaps—with potentially serious consequences.

The paperless laboratory is no longer a concept for the future, but a necessity. It is the only way to meaningfully link central interfaces, processes, and contexts and actively manage knowledge. Modern solutions such as LabThunder an important contribution to making this networking a reality in everyday laboratory work.

Knowledge management as a core component of laboratory asset management

Traditionally, laboratory asset management focuses on the physical management of equipment: inventory, maintenance schedules, calibration intervals. This perspective falls short.

Modern laboratory asset management also encompasses the knowledge level:

Operational experience: What problems have arisen in the past? How were they solved? Which solutions did not work?

Methodological knowledge: Which analytical strategies have proven effective for specific issues? Which matrix effects are known?

Maintenance history: Which components were replaced and when? Were there any abnormalities before or after the replacement?

Training status: Who is qualified for which systems and methods? Where are there gaps in knowledge within the team?

Troubleshooting database: Which symptoms indicate which sources of error? Which diagnostic steps are useful?

These levels of information are inextricably linked to the physical asset. A device without the associated knowledge is an incomplete asset. Investing in an LC/MS system involves not only hardware and software, but also the systematic development and documentation of knowledge about this system.

In this context, the paperless laboratory becomes an enabler: information is available digitally, searchable, structured, and accessible directly on the system. Instead of searching through folders, notebooks, or email histories, employees can find relevant knowledge exactly when they need it.

Limitations of Excel and traditional LIMS systems

Many laboratories attempt to map test equipment monitoring using Excel or traditional LIMS systems. This approach works well for simple tasks such as maintenance planning, calibration dates, and equipment inventory.

However, when it comes to dynamic, context-related knowledge, these tools reach their limits.

Limitations of Excel

Excel spreadsheets are linear and static. They capture data, but not correlations. A test equipment monitoring Excel spreadsheet shows when maintenance is due—but not why a particular problem occurred during the last maintenance, how it was solved, and which employees were involved.

The link between device, event, cause, solution, and people involved is missing. Knowledge remains fragmented. Searching for relevant information is inefficient. Scaling to multiple devices and a growing team is virtually impossible.

Limitations of traditional LIMS

Traditional LIMS systems are primarily sample- and results-oriented. They manage analysis orders, measurement data, and approval processes. Their strength lies in the structured handling of routine analyses and data integrity.

Knowledge management in the narrow sense—recording troubleshooting experiences, best practices, methodological findings—is not their core function. Although some systems can record comments and notes, they usually lack the search and linking functions that are necessary for systematic knowledge management.

The role of the paperless laboratory

The paperless laboratory is more than just digital document storage. It creates the technical basis for networked, searchable knowledge systems.

In a consistently paperless laboratory, all relevant information is digitally recorded and linked together:

- Device documentation and operating instructions

- Method descriptions and validation reports

- Maintenance logs and service reports

- Troubleshooting logs and error analyses

- Training certificates and qualification documents

The advantages are obvious: faster access, better searchability, location-independent availability, automated reminders, and workflows. But the decisive added value comes from linking this information. A troubleshooting entry is not just an isolated note, but is linked to the affected device, the method used, the people involved, and possibly similar historical incidents.

This networking transforms individual pieces of information into systematic knowledge.

Practical elements of a structured knowledge management system

Effective knowledge management in the laboratory is based on several interrelated elements:

Systematic event recording

Every relevant incident—be it a deviation, a technical problem, or an unexpected observation—is recorded. Not as a bureaucratic obligation, but as a building block of knowledge. The decisive factors are symptoms, cause analysis, measures taken, and their effectiveness.

Troubleshooting database

A structured collection of typical problems and proven solutions. When peak tailing occurs, when retention shifts, when the ion signal weakens—there are possible causes and diagnostic steps for all of these symptoms. These do not have to be reinvented every time.

Method notes and best practices

Which settings work particularly well for certain substance classes? Which columns show optimal separation for which matrices? Which preparatory steps are critical? This empirical knowledge must be systematically documented and made accessible.

Service history and technical interventions

Every component replacement, every adjustment, every calibration is documented—not only as proof of maintenance, but as part of the device's history. Patterns become apparent: Which components wear out faster? Which problems occur more frequently after certain interventions?

qualification matrix

Who is authorized to operate which device? Who is trained in which methods? Where are there gaps in knowledge that need to be filled? Systematic competency management prevents critical analyses from being performed by insufficiently qualified individuals.

Lessons learned processes

After major incidents, after method developments, after audits: What have we learned? What should be done differently? These findings must be fed back into the system—in the form of updated SOPs, supplemented troubleshooting entries, or additional training.

Conclusion: No longer starting from scratch

Modern laboratories invest considerable sums in analytical technology. An expensive LC/MS system is a strategic investment in analytical performance. However, this investment only realizes its full value when knowledge about operation, methodology, troubleshooting, and optimization is managed just as professionally as the device itself.

Knowledge management is not a luxury, but an integral part of laboratory management and quality management. It reduces risks, increases efficiency, improves quality, and strengthens compliance. It prevents laboratories from having to start from scratch every time there is a change in personnel, an unexpected disruption, or a new methodological challenge.

The combination of laboratory asset management, digital systems, and consistent knowledge management creates the basis for stable, efficient, and future-proof laboratory operations. At a time when analytical requirements are increasing, regulatory pressure is mounting, and skilled workers are becoming scarce, systematic knowledge management is no longer an option—it is a necessity.

LabThunder:

✅ Compliant with ISO 17025, GMP/GLP, and ISO 15189

✅ Digital logbooks instead of paper chaos

✅ Thunder AI central intelligence for errors & questions

✅ Smart & predictive maintenance prevents downtime

✅ Greater independence from external service providers

✅ Up to 50% fewer service calls

✅ Easy to use - no IT required

Contact us today for a free demo:

%20new.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)